How does pulmonary emphysema develop?

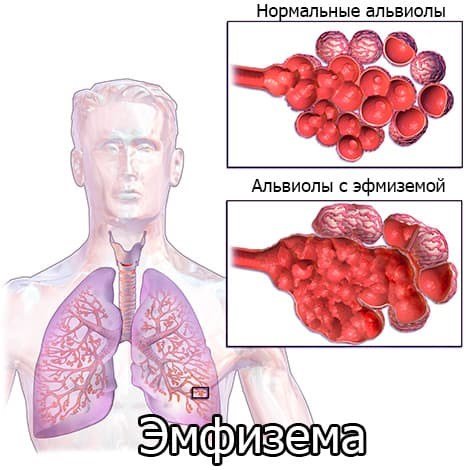

What is emphysema?

This is a persistent increase in the air spaces of the lungs distal to the terminal bronchioles with destruction of the alveoli.

Signs of mild pulmonary emphysema are detected at autopsy in 2/3 of cases.

The main causes and signs of pulmonary emphysema:

- Hypoplasia due to bronchopulmonary disease

- Atrophy, i.e. loss of parenchyma. This form is observed, for example, in smokers (smoking is the most important etiological factor) and in older people (senile emphysema)

- Increased airiness of the lungs or destruction of the peripheral airways (valve mechanism, end-stage inflammatory diseases, a1-antitrypsin deficiency).

- Shapes:

- Centrilobular emphysema (in smokers, often associated with chronic bronchitis, associated inflammatory changes and fibrosis)

- Panlobular emphysema (a1-antitrypsin deficiency, McLeod/Swire-James syndrome, familial form)

- Paraseptal emphysema.

Lifestyle correction for patients with emphysema

If persistent emphysema is detected on an x-ray, lifestyle changes should be made to improve overall well-being and improve quality of life. The following activities are recommended:

- Quit smoking, as smoking is the main cause of COPD.

- Change your work activity (if it is related to the chemical, coal, flour milling and other industries that increase the risk of developing obstruction and other respiratory diseases).

- Move to an ecologically clean region or at least undergo treatment in a sanatorium once a year; you need to choose a dry and warm climate.

- Follow a hypoallergenic diet, as sometimes food can cause bronchial asthma and lead to bronchial obstruction.

- For any diseases of the upper respiratory tract, follow the doctor’s recommendations and strictly adhere to the prescribed therapy.

Pulmonary emphysema is the logical conclusion of a chronic obstructive process. The pathology is accompanied by significant changes in the functional state of the lung tissue and is clinically manifested by signs of respiratory failure.

As the process progresses and decompensates, cardiovascular disorders form. It is important to detect the first signs of emphysematous changes for timely lifestyle correction and prevention of serious complications. MRI is also an alternative technique.

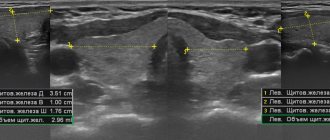

Which method of diagnosing pulmonary emphysema to choose: MRI, CT, X-ray

Selection method

- CT.

Why is a chest x-ray done for emphysema?

- The sensitivity of the method is low and is approximately 50% (mild forms of the disease may go undetected)

- Specificity is high (>90%)

- Deformation of the chest (barrel chest due to increased sagittal size, wide intercostal spaces; flattening of the costophrenic sinuses)

- Low standing and flattening of the diaphragm

- Depletion of peripheral pulmonary vascular pattern

- Vasodilation of the root of the lung

- Increased transparency of lung fields

- "Emphysematous (pulmonary) heart."

What will MSCT of the chest show for emphysema?

- Paraseptal pulmonary emphysema - bullous

- The basal segments of the lung are predominantly affected

- With panlobular emphysema, the architecture of the entire lobule is disrupted

- With centrilobular pulmonary emphysema, destruction of the alveolar wall is observed in the center of the secondary pulmonary lobules, the peripheral parts of the lobules and vessels are intact

- Areas of increased radiolucency (emphysema threshold is less than -950 HU; normal lung tissue density ranges from -750 to -900 HU).

- The cranial segments of the lung are predominantly affected.

- There are fewer vessels

- A special form of panlobular emphysema develops with a1-antitrypsin deficiency.

- Mainly affects subpleural and bronchovascular areas of the lung.

Emphysema in a 50-year-old man. On a plain radiograph, the chest is bell-shaped, the diaphragm is flattened, its level is low, and the vascular pattern of the lungs is depleted. Slight curvature of individual vessels. The heart shadow is reduced, the pulmonary trunk bulges.

Specific symptoms

- Chest X-ray: typical picture of regional or global increase in the transparency of the lung fields and depletion of the peripheral vascular pattern

- CT: destruction of the alveolar wall.

Diagnostic methods

An accurate diagnosis can be made to the patient by:

- X-ray, in which transparent areas filled with air are visible in the lungs;

- spirometry, which allows you to clarify the volume of inhaled and exhaled air. With emphysema, the second indicator is much greater than the first;

- peak flowmetry helps to clarify the expiratory flow rate when taking bronchodilators and without their use.

An additional method for diagnosing pulmonary emphysema is a blood test, which can be used to monitor the presence of an inflammatory process in the body and its intensity.

The set of necessary diagnostic measures depends on the condition of a particular patient and the need to detail the picture of his health.

Clinical manifestations

Typical symptoms of emphysema:

- Respiratory disturbance depends mainly on morphological changes and to a lesser extent on the type of emphysema

- Senile emphysema and increased airiness of the lungs are often asymptomatic

- Symptoms of pulmonary emphysema in “Pink Puffers” - patients complaining of difficulty breathing during physical activity, non-productive cough with relatively normal levels of gases in the arterial blood

- In “blue puffies,” breathing is normal, but the bronchi are affected, which is manifested by cyanosis and chronic recurrent bronchitis

- Signs of pulmonary hypertension

- Increased total lung capacity and residual volume; OFB1 and lung perfusion capacity are reduced.

Reasons for the development of emphysema

Impact of endogenous factors:

- Impaired blood microcirculation in the lung parenchyma;

- Changes in surfactant morphology;

- A1AT (Alpha 1-antitrypsin) deficiency;

- Hereditary predisposition;

- Respiratory tract diseases (especially chronic bronchitis);

- Aging.

Impact of exogenous factors:

- Impaired blood microcirculation in the lung parenchyma;

- Changes in surfactant morphology;

- A1AT (Alpha 1-antitrypsin) deficiency;

- Hereditary predisposition;

- Respiratory tract diseases (especially chronic bronchitis);

- Aging.

Lung tissue is an elastic frame, similar to a sponge. Small chambers that fill with air when you inhale and are emptied when you exhale are the alveoli. With emphysema, a finely porous sponge becomes coarsely porous and stretches, its fiber loses strength and collapses. The diameter of some alveoli expands, but other air chambers are destroyed. The area of functional lung tissue is reduced, and bullae appear - useless bag-like areas of the lungs that do not participate in gas exchange. Over time, in patients with pulmonary emphysema, the chest also becomes deformed - it expands and takes on a barrel-shaped shape.

Course and prognosis

- Complications include spontaneous pneumothorax and recurrent bronchopulmonary infections

- Restriction of pulmonary function correlates with the degree of changes in the lung parenchyma

- With an advanced form of the disease, the prognosis is unfavorable.

CT is necessary to quantify and classify emphysema. Centrilobular emphysema (a) is characterized by small nodular lucencies corresponding to swollen alveoli in the center of the acini. Panlobular emphysema (c) is characterized by generalized airiness and destruction of the pulmonary parenchyma. Transitional forms ( b ) between centrilobular and panlobular emphysema are often encountered. Paraseptal emphysema is common and usually has no clinical significance (d). On the presented tomograms it is combined with centrilobular emphysema.

Diagnosis of functional disorders

Performing functional tests during radiography is important for the differential diagnosis of irreversible changes in lung tissue.

With emphysema, despite the increased volume, there is no functional exchange of exhaust air. The dilated alveoli contain the same air. This leads to decreased blood oxygenation and clinical signs of hypoxia.

The following tests are used to determine radiological symptoms of irreversible functional changes:

- Sokolov method: a series of sequential photographs are taken at different phases of the respiratory cycle on X-ray film measuring 13x18 cm, after which the deflection of the diaphragm is compared with a ruler;

- The targeted imaging method is a targeted diagnosis of the area of local emphysema: several pictures are taken while inhaling deeply, then exhaling, holding the breath, and then the results are compared;

- Sheath method: The right lung is closed so that the dome of the diaphragm is below the lower edge of the sheath. A series of photographs are then taken in which the distance from the disc to the diaphragm during the inhalation, exhalation and breath-hold phases determines the degree of lung deflection.

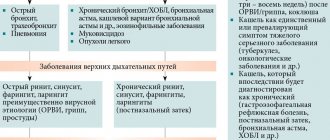

What diseases have symptoms similar to pulmonary emphysema?

Pulmonary cyst and other cystic lesions

— The wall structure is visible

Bronchial asthma

— There is no destruction of parenchyma

— Increased airiness may subside after the administration of bronchodilators

Bronchiolitis obliterans

— There is no destruction of parenchyma

— Perfusion of lung tissue is mosaic

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis

— Occurs almost exclusively in women during the reproductive period

— Thin-walled cysts

- Chylous pleural fluid

Histiocytosis X

— Nodular changes

Increased transparency on x-rays: what is it?

X-ray emphysema changes are more common and affect the left and right lungs. However, sometimes with local bronchostructure one can detect compensatory emphysema in the form of increased pneumatization around pneumosclerosis and fibrosis of the lung tissue, areas of atelectasis and other non-functional structures. In this case, areas of increased airiness appear on the radiograph around the local darkening.

The following types of emphysema are determined by radiographs:

- Primary - occurs as a result of narrowing of the lumen of the bronchi. This is an early form in which changes undergo regression.

- Secondary - chronic emphysema, in which blockage of the bronchi occurs with pathological contents.

- Tertiary - local pneumothorax, in which there is increased aeration in some parts of the lung fields.

If an x-ray shows that half of the chest is suffocated, it is called a pneumothorax.

This pathology often complicates the course of bullous pneumothorax. The lung is pressed against the root, due to which its structure is disrupted. The organs of the mediastinum (heart, great vessels, esophagus) move to the healthy part of the chest.

Clinically, the patient exhibits symptoms of acute respiratory failure and requires surgical treatment: puncture of the pleural cavity.

Mediastinal emphysema, or pneumomediastinum, is a pathological condition consisting of air infiltration of mediastinal tissue [4].

It is believed that spontaneous mediastinal emphysema (SEM) is a rare, independent disease characterized by a benign course and occurring without specific causes; it affects mainly young men [9, 19, 23, 36].

The first mention of SES dates back to 1617, when the midwife of the Queen of France, Louise Bourgeois, in her memoirs described the sudden swelling of her neck during childbirth [12]. This pathological condition was first described by Rene Laennec in 1819 in his treatise “On Listening with a Stethoscope” [24]. SES as an independent disease was first reported by Louis Hamman [5, 10, 19, 23, 25] in 1939. He described rough crepitus, synchronous with heartbeats, which is auscultated along the left edge of the sternum in the third to sixth intercostal spaces, not excluding and other areas in a sitting position. This clinical symptom is called Hamman's symptom.

The pathophysiology of this disease, based on experiments on laboratory animals, was described in 1944 by M. Macklin and S. Macklin [5, 10, 23, 25]. In an experiment on animals, they showed that SES occurs as a result of a sharp decrease in the pressure gradient between the alveoli and the interstitial tissue of the lungs, which leads to rupture of the alveoli. The described mechanism, in combination with pathological changes in the alveolar-capillary membrane and/or interstitial tissue of the lungs, can lead to a breakthrough of the alveoli into the interstitial space [31]. Breakthrough of the alveoli into the pulmonary interstitium leads to the accumulation of air in it, which spreads along the pressure gradient, perivascular and peribronchial, centripetally to the hilum of the lungs, and then into the mediastinum (Macklin effect) [20]. This occurs because the pressure in the mediastinum is lower than in the periphery of the lungs. Most authors agree that the disease occurs as a result of rupture of the terminal alveoli located at the root of the segment (lobe) of the lung and adjacent to the loose tissue surrounding the vessels and bronchi [5, 16, 23]. Once in the mediastinum, the air can spread to the cellular spaces of the neck, soft tissues of the chest, into the cavity of the cardiac membrane, and even (depending on the amount) into the retroperitoneal cellular space [8].

The frequency of SES in hospitalized patients varies, according to various sources, from 1:3578 [16] to 1:44,511[25].

There are different trigger mechanisms or factors that contribute to the occurrence of SES. I. Macia et al. [25] consider it advisable to divide these factors into: predisposing - bad habits and/or diseases in history that create conditions favorable for the development of the disease, and provoking - conditions that immediately precede the onset of SES.

Many authors include pulmonary diseases such as bronchial asthma [5, 9, 16, 19, 25, 29], inflammatory diseases of the upper respiratory tract [5, 19], idiopathic fibrosing pulmonary diseases [9], chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases as predisposing factors. [9]. Of the diseases listed above, according to publications in the world literature, only bronchial asthma is considered as a predisposing factor in the development of SES by almost all authors [5, 9, 16, 19, 25, 29, 35, 36]. J. Chapdelaine et al. [11] established a history of this disease in almost 50% of patients, A. Newcomb and C. Clarke [29] - in 39% of patients with SES. It should be noted that in the world literature, authors rarely associate the development of SES with bullous pulmonary emphysema. A.G. Vysotsky [2] described 4 cases of pneumomediastinum as a complication of local bullous emphysema. I.I. Platov and V.S. Moiseev [4] believe that the development of SES is associated with the same reasons that lead to the development of spontaneous pneumothorax, namely bullous disease, cystic lung formations of congenital origin, and respiratory inflammatory diseases.

Some authors believe that smoking is a predisposing factor in the development of the disease [9, 25]. J. Macia et al. [25] compared the number of smokers with SES with the number of smokers among the population of Catalonia (Spain), which was 34.1 and 37.5%, respectively. I. Abolnik et al. [6] noted that the number of smokers among patients with SES differed slightly from those in the general population.

Many provoking factors have been described that can directly cause the development of the disease. It is worth highlighting the Valsalva maneuver, intense coughing, sneezing, severe vomiting, hysterical screaming, childbirth, defecation, physical activity, bronchospasm, spirometry, playing wind instruments, blowing up balloons, using inhaled drugs [1, 5, 9, 10, 18 , 23, 25, 26, 28, 32].

In a report by M. Caceres et al. [9] the dominant among the provoking factors was vomiting, which preceded the onset of the disease in 36% of cases; the second most common factor was an attack of bronchial asthma; this condition was observed in 21% of patients. Cough is also one of the common trigger factors, and according to various sources, it precedes SES in 7.3% [25] and in 40% of cases [28]. The occurrence of SES due to diabetic ketoacidosis [36], chemotherapy [34], and Hodgkin's disease [21] has also been described.

However, it is not always possible to identify predisposing and/or provoking factors; SES often occurs at rest [9].

The variety of symptoms in the clinical manifestation of SES has been reported by many authors [25, 36]. The most common triad of clinical symptoms is chest pain (which is the most common and constant symptom), difficulty breathing, and puffiness of the neck [1, 5, 15, 16, 19, 25, 29, 35, 36]. I. Abolnik et al. [6] noted the presence of chest pain in 88% of patients with SES, I. Macia et al. [25] - in 85%, M. Gerazounis et al. [16] - in 72.7%, G. Koullias et al. [23] - in 66.6%, M. Caceres et al. [9] - in 54% of patients. The patient may also complain of pain in the throat, back, shoulder, lower back, weakness, dysphagia, odynophagia, rhinophonia, and change in voice timbre. Some authors include cough as a symptom of the disease, although it is also a factor provoking the occurrence of SES [23]. M. Caceres et al. and G. Koullias et al. identified cough as one of the symptoms of the disease; it was noted in 41 and 32% of SES’s own observations and was, respectively, the second and third most common symptom after chest pain [9, 23].

Of the clinical symptoms of the disease identified during physical examination, subcutaneous emphysema of the soft tissues of the neck and/or chest is most often noted [1, 2, 5, 7, 16, 25, 36]. Depending on the amount of air entering the mediastinal tissue, soft tissue emphysema can spread to the face and lower chest, but this is rare [5]. In a report by I. Macia et al. [25] in 95% of patients with SES, subcutaneous emphysema of soft tissues was determined by palpation, in 66% of patients - in the neck, and in 29% of patients - in the chest wall. J. Jougon et al. [19] stated the presence of this symptom in 100% of patients with SES. M. Gerazounis et al. [16] described the presence of rhinophony (nasal tone) in 5 patients, which was noted together with emphysema of the soft tissues of the neck and developed as a result of dissection of the tissues of the retropharyngeal cellular space with air. This symptom is quite rare, but there are observations in which it serves as the first manifestation of SES and the main clinical symptom of the disease [17].

Hamman's symptom cannot be called specific for SES, since, according to Yu.V. Haleva [5], such crepitus can be heard in left-sided pneumothorax without mediastinal emphysema, as well as in bullous emphysema of the lingular segments, pneumoperitoneum with a high diaphragm, and gastric dilatation. The prevalence of Hamman's symptom in patients with SES, according to various sources, varies from 0 to 56% [6, 9, 10, 15, 23, 25, 29, 36].

With pneumomediastinum, patients may also experience a decrease in cardiac dullness and deafness of heart sounds during auscultation. I. Abolnik et al. [6] in 2 patients with SES the presence of paradoxical pulsus was noted. Most patients may have one or more symptoms, but sometimes objective examination fails to identify any symptoms [5].

The main methods for diagnosing SES are chest x-ray in frontal and lateral projections, breast CT and x-ray contrast examination of the esophagus.

A. Yellin et al. [36] indicated the need to perform radiography (as a routine method of primary diagnosis) in all young patients with chest pain of unknown origin and difficulty breathing. According to many authors, this research method turned out to be informative in the vast majority of patients with SES [6, 16, 23, 36], while they emphasize the need to perform the study in two projections - frontal and lateral, because with a small accumulation of gas in the mediastinum during survey X-ray of the chest in a direct projection may not reveal pneumomediastinum [23, 25].

When pneumomediastinum occurs, x-rays reveal clear bands or gas bubbles surrounding the mediastinal organs, elevating the mediastinal pleura and often extending to the neck and/or chest wall [14].

S. Bejvan and J. Godwin [8] report that with AP radiography, free gas in the mediastinum is often detected along the left contour of the heart and covers the inner surface of the mediastinal pleura, creating a clearly visible pleural line lateral to the pulmonary trunk and aortic arch. On radiographs in the lateral projection, free gas forms lines of clearing along the contours of the ascending aorta, the aortic arch and its branches, the pulmonary arteries and the trachea with the main bronchi [8]. Gas is also localized along the line of attachment of the diaphragm to the sternum, along the thymus gland and brachiocephalic veins [13].

Polypositional radiography is the main and very effective research method for this disease, but if there is gas infiltration of the soft tissues of the chest wall, then its information content is reduced to almost zero. In such situations, as well as in case of suspicion in relation to diseases with a similar clinical picture and if it is necessary to establish the cause of the disease, if the X-ray method is insufficient, it is advisable to perform a breast CT scan [30]. T. Kaneki et al. [20] noted that in 30% of patients with SES, radiography failed to detect pneumomediastinum; the final diagnosis was made by chest CT. G. Koullias et al. [23] performed CT after an initial X-ray examination in all 25 patients, although they considered X-ray the “gold standard” for diagnosing SES, since both of these diagnostic methods turned out to be informative regarding pneumomediastinum in 100% of cases. CT is undoubtedly the most effective method for diagnosing pneumomediastinum [20], since with its help the presence of gas in the mediastinum is easily detected and its anatomical localization is well determined in cross sections. However, it should be noted that in terms of ease of implementation and radiation exposure to the patient, this method is inferior to radiography; we should also not forget about the economic aspect. A. Newcomb and C. Clarke [29] believe that if pneumomediastinum is determined using radiography and there is no suspicion of the presence of any serious disease as the cause of this pathological condition, then we can limit ourselves to only this diagnostic method.

In some cases of SES reported in the world literature, X-ray contrast examination of the esophagus was performed. This additional diagnostic method was used in situations where it was necessary to exclude the presence of such a dangerous condition as esophageal rupture. A water-soluble contrast agent and/or barium sulfate suspension is used [15, 16, 19, 36]. D. Weissberg [35] used this research method to exclude esophageal rupture if the occurrence of SES was preceded by vomiting.

Additional research methods for this disease include esophagoscopy, bronchoscopy and electrocardiography. These methods are auxiliary and are used to confirm the diagnosis of SES in doubtful situations.

Differential diagnosis of SES is carried out with diseases of the cardiovascular (acute coronary syndrome, pericarditis), respiratory (spontaneous pneumothorax, pulmonary embolism, perforation of the tracheobroncheal tree) and digestive (spontaneous rupture of the esophagus) systems [32].

According to foreign authors [15, 25, 29, 35, 36], the optimal period of inpatient observation and treatment of patients with SES ranges from 2 to 5 days.

SES responds well to conservative treatment, which includes bed rest, analgesia and oxygen therapy [6, 9, 15, 23, 29]. In this case, a fairly rapid regression of symptoms is observed and in most cases complete resolution of pneumomediastinum occurs by the 8th day [29, 36]. Usually, soon after the alveoli break into the pulmonary interstitium, they collapse, as the pressure in them decreases and the flow of air stops [19]. G. Koullias et al. [23] all patients received antibacterial prophylaxis for mediastinitis. They used third-generation cephalosporins with the addition of clindamycin to therapy for suspected esophageal perforation and when the disease was accompanied by fever and leukocytosis. Very rarely, emphysema of the tissue of the neck, chest and abdominal walls, and face progresses and tense pneumomediastinum develops. In this case, the mediastinum, according to Sauerbruch, “swells up like a ball”, the thin-walled main veins of the mediastinum are compressed with a drop in cardiac activity, respiratory failure and possible death [3]. In such situations, an upper mediastinotomy according to Tiegel is indicated with tunnelization of the pretracheal fat to the level of the tracheal bifurcation with drainage of the mediastinum and subsequent aspiration, which ensures decompression of the mediastinum [4]. J. Moore et al. [27] in infants with tense mediastinal emphysema, mediastinal drainage was performed through a subxiphoid approach. For decompression of soft tissues and the mediastinum in this complication, some authors propose suprasternal puncture of the mediastinum and sternotomy [33], puncture of the supraclavicular areas [6] and tracheostomy [22]. If, despite these measures, an increase in tense mediastinal emphysema is observed, an urgent transpleural wide mediastinotomy is required [4].

Isolated observations of relapse of SES have been described [16, 25]. A. Yellin et al. were the first to describe relapse of the disease in the literature. [36], they observed patients for 52 months after discharge from the hospital; the recurrence of mediastinal emphysema in one patient occurred 14 months after the first episode without predisposing causes.

Thus, spontaneous mediastinal emphysema is a disease that most often affects young men of working age. Its occurrence requires differential diagnosis with a number of serious pathological conditions. In rare situations, tension mediastinal emphysema can lead to hemodynamic and respiratory compromise.